reading sylvia plath doesn’t make you radical babes.

on the shallow woman writer.

there are phrases i reach for so often it is as though they are old, reliable lovers of mine. one of them is you lie like a rug woman; i reach for her whenever i surprise myself which has, of late, been often. i’m in my early twenties. there are many rugs. many lies. another common exclamation of mine is purely accusatory, devoid of all endearment:

who will be bertha mason this time?

it is usually accompanied by a sigh and the cracking open of a book they have been telling me is a classic since before i could read.

the second sex. the handmaids tale. pride and prejudice. the bell jar.

it is shorthand for: which black woman will this white writer trod on as she tries to climb the rungs of her own self-grandeur? how, in all her vanity and self-occupation, will she leave us all behind?

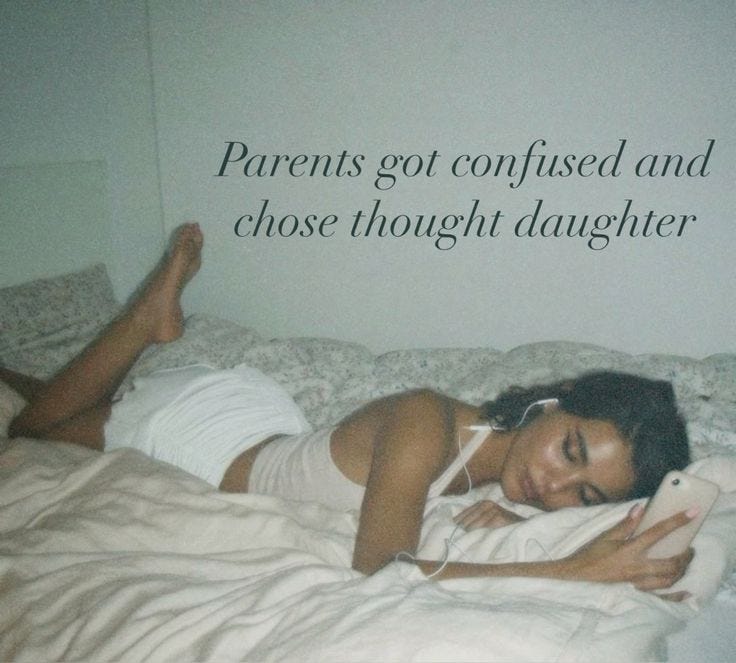

i first met bertha mason when i was reading english at university. that introductory seminar set the stage for what the rest of my first year was going to be like. for this particular module, we were studying the novel as a form and its evolution in british literature post the 1800s specifically. that meant being assigned the white girl bible (known in layman terms as jane eyre) for reading. i discovered quite quickly that the only thing more insufferable than a ‘thought daughter’ was a gaggle of them. to anyone looking at the apostrophed phrase above in confusion, know that i envy you.

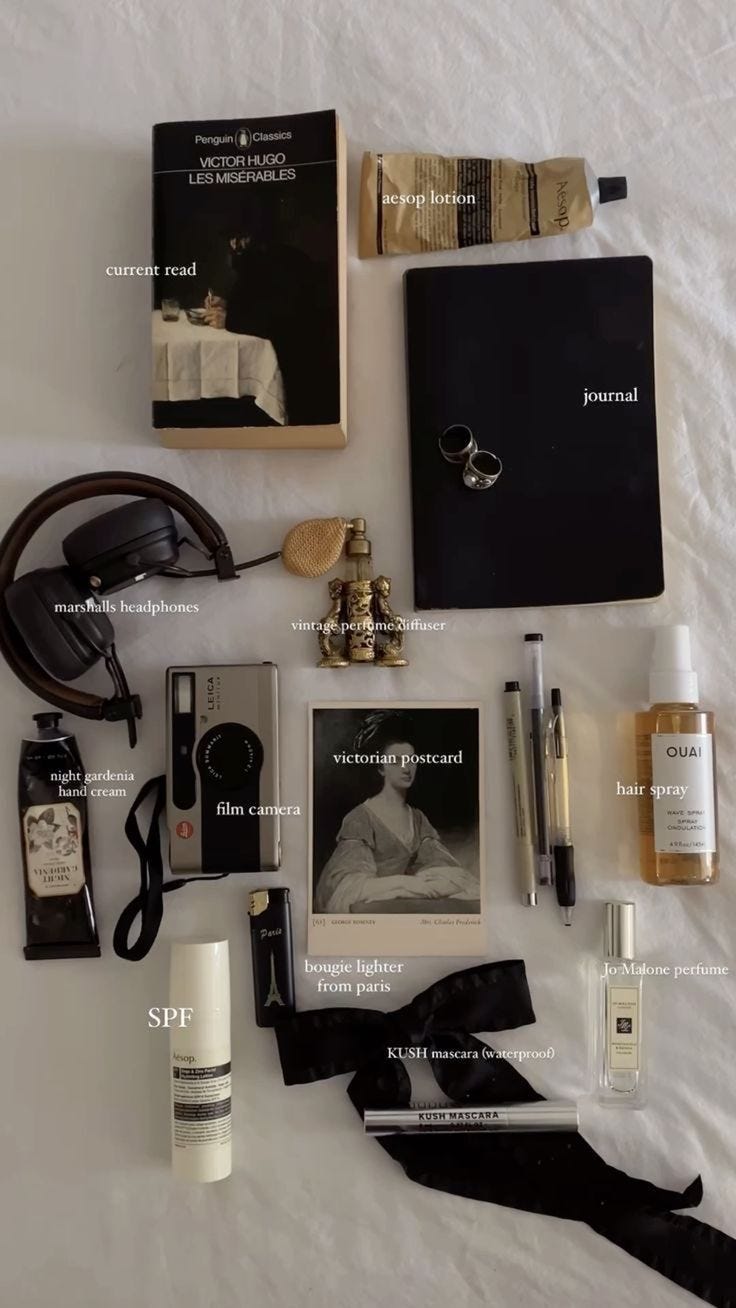

put simply: the thought daughter is an amalgamation of self-aggrandizing pseudo-intellectual tropes that boil down to i read a lot of women’s literature and i own more tote bags with joan didion’s face printed on them than is proper. look at me perform my intelligence and misery by taking pictures of my copy of the bell jar with tear stains littering the page. she knows every lana rey lyric by heart and lives on pinterest and shits bookmarks. she thinks herself better than you, never mind that if you held a gun to her head and asked her to name five black or brown authors who aren’t dead, she’d have to call her family to start making funeral arrangements.

she also probably has a literature degree, which is where i learned to interact with this particular brand of woman. they didn’t have a name back then; you could tell who they were from their loafers and moleskin leather journals.

the micro-aggressions began before we even made it through the door; the first thing one of those girls ever said to me was i’m sorry if you catch me staring; i’ve never seen someone in a headscarf in person before! everyone in my village looks like me. leicester is so diverse!

the only other non-white student waiting for class to begin was a pretty bengali girl who looked at me with wide eyes, the question in them clear as day:

did she just…

she did.

(she would later become one of my best friends).

i remember staring at little miss village blankly in response to her nauseatingly saccharine smile until she got uncomfortable enough to pretend to check her phone. it wouldn’t be the first time that day i made her want the ground to swallow her whole. the next came during the seminar itself. our professor, a man as bald as he was boisterous, asked us to share our first impressions of the book he’d assigned, ready to get the discussion going.

the reviews were, of course, blindingly positive.

i loved it so much. how bold of charlotte to write a self-actualized woman at that time, how radical. cue a room filled with earnest nodding and whispered i thought the exact same thing, she’s just so brilliant. i remember sitting there watching these bobbleheads perform their agreement and exultation of bronte with barely contained annoyance. it must have emanated from me the way dior sauvage does the pores of a man who is about to ruin your life; with persistence. the story of jane eyre is recognisable enough- poor, abused white girl becomes a governess, escapes her circumstances and falls in love with a conveniently wealthy man with poor manners.

our professor had listened to all this tactless, self-celebratory clitoris rubbing in dutiful silence. our eyes met at one point after the fifth girl in the room had described the novel as a work of ‘radical feminism’. after they were done, he looked at me with a barely contained smile on his face.

what do you think ayan?

he wanted to start a fight; he saw my black face and knew that i was the only one who was going to have something different to say. he wanted me to have the floor. after all this time, i still haven’t been able to decide if it was because he wanted me to advocate for myself, or if he was simply bored.

i was not born sharp tongued. i only wield my words like blades now because i have been in this exact predicament so many times. bravery is a muscle. the first time you speak up in a room full of strangers, you feel fear press up on your chest like a middle aged man during rush hour on the train. you feel naked, desolate. alone because you are. the second time is worse because you remember how it felt that first time but by the third, it’s old news. you know how to read the faces trying so hard to stay blank but that can’t quite erase the petulance from their set jaws, eyes barely resisting the urge to roll in dismissal.

i disagree with the assertion that the novel is a great work of feminist fiction. i think it’s dismissive and crude in its representation of black people, specifically black women. take, for instance, how bronte characterizes bertha mason-

sorry interrupted the village girl but whose bertha again?

i should be given a medal for the self-restraint i displayed. instead of jabbing her in the eye with my new fountain pen, i took a deep breath and kept talking like i hadn’t heard her speak.

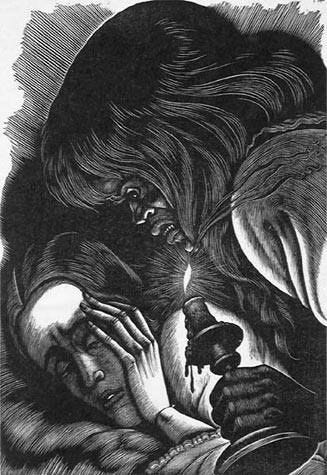

coded as a black woman, bertha mason is the first wife of the book’s male lead lord rochester. she is framed as the villain of the piece, a possessed, demonic threat to jane; her face is ‘savage’ and ‘blackened’. we are meant to fear her instead of feeling empathy for her, despite the fact that she has been kept prisoner by her cunt of a husband and locked away in an attic. reduced by bronte to a ‘strange wild animal’, bertha mason became representative to me of the way white women writers are so often forgiven for their callousness in dealing with people beyond themselves because look: the white woman gets what she wants at the end of the novel. isn’t that enough?

that’s how everyone wrote about black people back then though, one of the thought daughters said. you can hardly hold that against her.

would you have accepted that as an answer if we were interrogating the work of a misogynistic male writer? you wouldn’t? then what makes leave your modernity at the door a good enough reply when we are dealing with entrenched anti-blackness in these novels?

i do not understand why we talk about the politics of the past as if the moral questions presented to people back then were any different to the moral questions we still struggle with now.

just as in bronte’s time, there are those who seek to dehumanise and legislatively limit the rights black people have fought to protect. we are still in the midst of a battle for equity and emancipation. the prison industrial complex holds our young men and women hostage; it is slavery by a different name. black mothers are still four times more likely to die giving birth than their white counterparts due to medical negligence. we have men in the white house arguing to make a registry to ‘keep tabs’ on people with autism. just as people watched hitler perpetuate a violent genocide the likes of which the world had never seen with startling, bone-chilling efficiency, we turn on the news and see the devastation israel is raining down on Palestinians day in, day out.

in short: the choice to be an insensitive racist has and will always exist. the sour truth you cannot swallow is that your icon might have been one.

sylvia plath is another venerated to something like a God by the bookish white thinker. her work is just as demoralising to engage with. the bell jar is not only so laden with violent racism, it astounds me to imagine how plath would react to seeing her book in my black hands (‘dusky as a bleached-blonde negress’ was a description that stuck out to me in particular, as did the way esther physically assaults the black man who serves her dinner at the mental health institution she finds herself in), but it is also a novel that is almost masturbatory in its self-involvement politically. to phrase it better- the only victim plath could ever view as worth trying to understand was a white woman, the only pain she cared to express was her own. she and women like her are all that matter- everyone else was a negress to fear or a beast to beat. plath was victimised by the misogyny she faced; plath victimised the black characters trapped within the pages of her novel. she is both victim and villain in that way; those truths can co-exist.

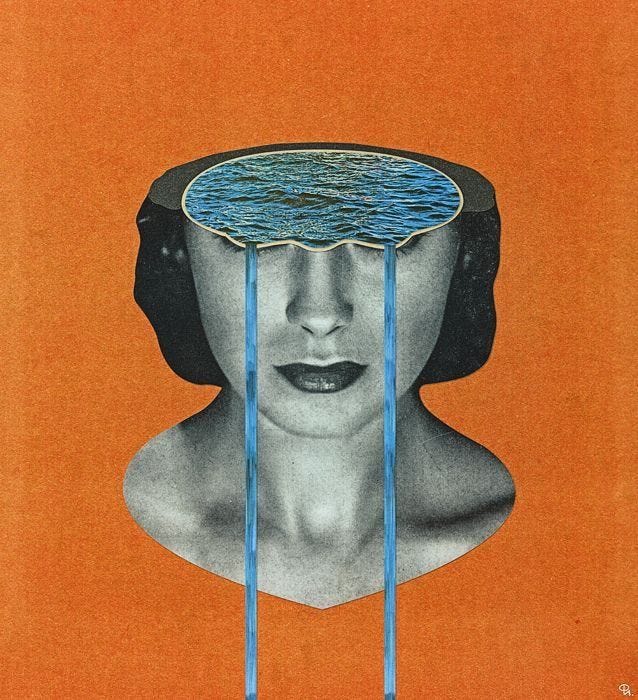

i have always wondered what it was about her that drove so many young women to cultish admiration. was it her death, our culture’s morbid fascination with tragedy and the white victim? or did it speak to something else, something more hidden? my theory in observing how the white writers of this moment have reacted to the world we are watching burn revealed an alternative reading on the cult of plath and the white feminist: they resonate with these women not only for their perceived writerly prowess, but also because they represent the political selectivism they subscribe to.

let’s return to the thought daughter for a moment.

there are many lurking on this platform. scroll through their pieces. how many essays are there dedicated to putting their multiple neuroses on display with the hopes of being deemed honest and authentic by strangers on the internet? how many talk about the mental illness’ awaiting women artists, aestheticizing suffering in the hopes of going viral? look at their pages and see if you can find even a single post saying something that is actually politically charged. they will be the first in line to buy a new suzanne collins novel. they’ll film themselves on the brink of tears as they share their heartbreak at what the children of the districts are put though by the capitol. those same eyes have seen the videos of Palestinian fathers carrying the remains of their dead children in plastic bags like mince meat from the butchers, and kept scrolling. ask them about what is happening in lebanon or what their tax money has made possible in somalia. margaret atwood lifted from the traumatic histories of black and brown women’s lives for her books and then called it speculative fiction. we only exist in the background to them.

everything is dystopian because they have never looked outside long enough to see that this is our reality; they’re too busy filming what’s in my bag videos set to chopin’s prelude in e minor to contend with something that requires as much self-interrogation as intersectionality. they spend their evenings writing personal essays because all they care to study is themselves. and then they wonder why their prose has no bite. no teeth. people used to fear writers. our words had power behind them, and actual clear eyed radicalism that could shift entire political ecosytems; the white people sat listening to baldwin debate william buckley at oxford must have felt like their skin was being sheared off every time he spoke.

all we are left with now are thought daughters who don’t actually want to think that much at all. when the revolution comes, they’ll be too busy trying to save their copies of the handmaids tale from the government buildings we’ll burn to the ground.

rent free is a subscriber supported platform. if you can, consider upgrading to help keep this newsletter independent of sponsorships and advertisements. every single paid membership helps me invest more time into rent free without having to compromise my creativity by finding a ‘money’ job. thank you as ever for the time you’ve spent with my work x

I've shied away from sylvia plath for most of my life and I think I will stay away. I also have had the amazing privilege of having read wide sargasso sea thank god

this is so fucking brilliant