we are all dehydrated.

on the thirst epidemic and the death of decorum online.

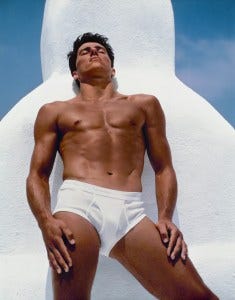

in 1982, calvin klein launched its first pair of men’s briefs with an advertising campaign featuring olympian pole vaulter tom hintnaus. shot by bruce weber, the campaign made the athlete the first face of calvin klein underwear in a shoot that led to bloomingdale’s selling $65,000 of calvin briefs in just a fortnight; it’s estimated that total gross sales from that first year culminated in about $4 million for the company.

being chosen to represent calvin klein has always been a marker of cultural currency and cool. the perfect calvin model is sexy in that practiced, homogeneously euro-centric way: the women are thin, the men athletic in build, more times than not white and young. you must desire them and desire to be with them at the same time.

the styling is suggestive and risque, yet simple. smoky bedroom eyes, tussled curls, jean fly open, that iconic CK waistband calling out like a flag to a new world. calvin klein trades in desire, our libidos being courted as aggressively as our wallets.

sex sells darlings, and very few companies have baked it more successfully into their brand identity and marketing than calvin klein.

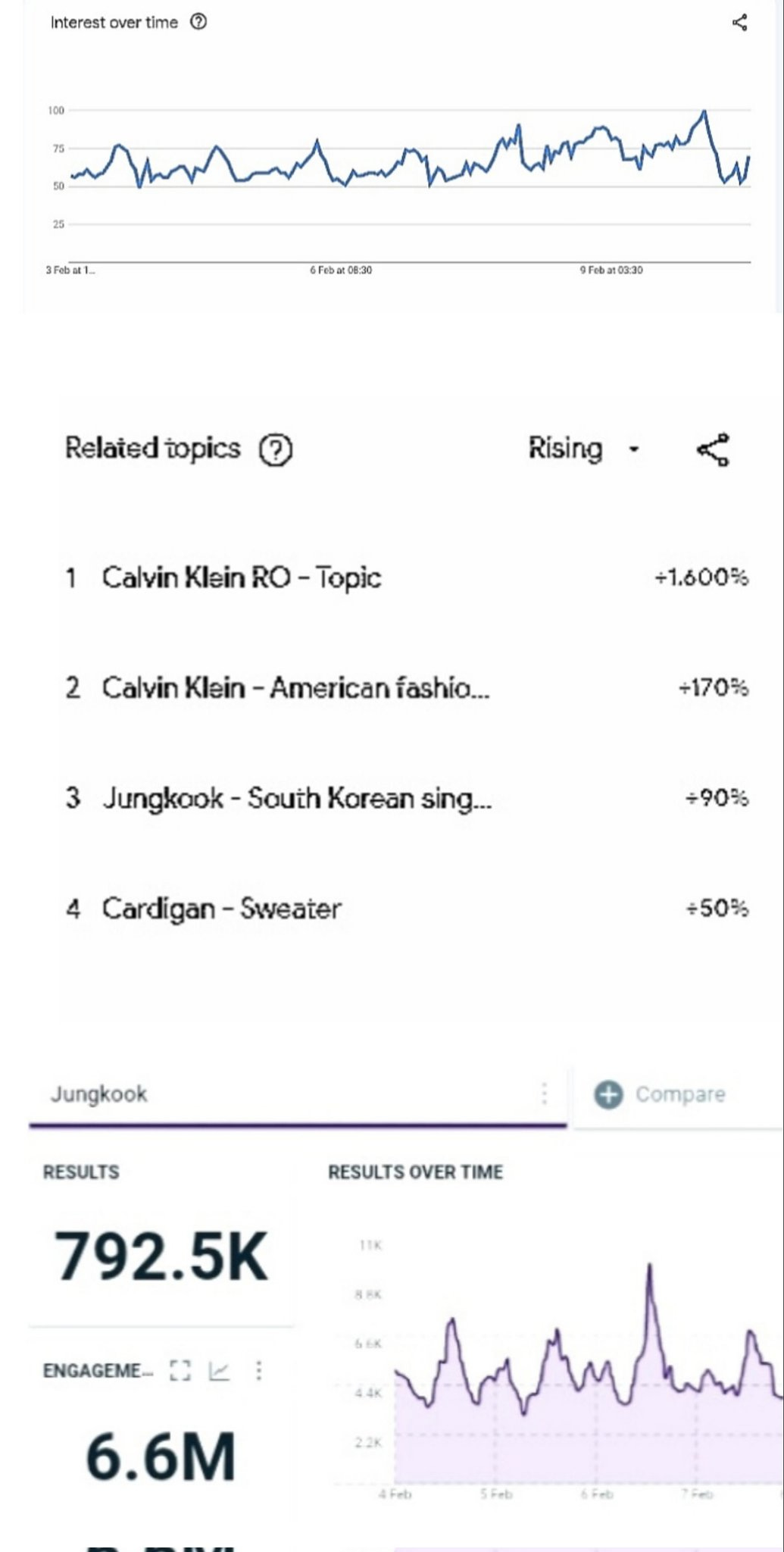

justin bieber, shawn mendes, the kardashians, michael b jordan, jungkook of BTS, most recently bad bunny- the list of celebrities the brand has courted for campaigns over the years is truly extensive. it’s a simple enough business plan. take the hottest young star and strip them of clothes. plaster them half naked all over billboards and watch as their fans descend into a frenzy.

in this digital age, watch as the brand’s social media teasers are edited into fancams set to sultry bedroom pop (recently, jungkook’s collab with the brand went viral nearly a year after it was released because people on twitter saw the images and confused him for - and i’m not even joking- a really sexy butch.

the thirst tweets that ensued helped the brand reach a global peak of 100% on Google for the first time in months. he ended up also being the highest rising and related topic (+90%) associated with the brand, generating over 6 million engagements on twitter in a single week. south korea needs to free our androgynous icon. he’s served enough, clearly).

when calvin klein was starting out, there was a conservatism that was palpable in the audiences they were marketing to. they were branded salacious, ungodly, sinful. the american family association (a conservative christian group) said it would boycott all retailers who sold calvin klein jeans following their 1995 meisel shoot featuring kate moss. bill clinton publicly criticized the brand for it’s overt sexualising of young women (pot meet fucking kettle) with the company even being investigated by the justice department’s child exploitation and obscenity section, the charges eventually dropped after calvin klein proved that all of the models featured in their campaign were of age (we’ll get to klein’s problematic love for a 'young, fresh’ face soon).

people were almost fanatical in their reactions to the images calvin klein was starting to become synonymous with. it was okay to hint and tease at sex, but explicitly selling it meant normalizing desire in way the american consumer couldn’t yet publicly accept. that doesn’t mean sex hasn’t always been a part of the way we consume popular culture. it was a silent film from 1915- ‘a fool there was’ -that gave us the very first sex symbol with theda bara’s exoticised performance. they may have worn more clothes, but the celebrities of that era were the training ground for how we consumers were encouraged to view the ‘star’.

objectification of the celebrity has always gone hand in hand with the exultation of them. people magazine’s ‘sexiest man alive’, the tabloid’s obsession with paparazzi beach pics of the angelina jolie’s of the world, the never ending tiktok commentary on who has gotten work done and who hasn’t-and thus who looks good and appetizing to us and who doesn’t: we can’t stop talking about how these people look and approximating their worth with how fuckable they are.

we really do live in a lust-propelled economy. take television for instance. hollywood seems intent on staying planted on the dicks of uncultured studio execs with no respect for the form, slowly killing the medium with vapid reboots and immediate cancellations. marketing isn’t marketing the way it used to (precisely because those selling the product no longer seem to be interested in it) which means fans have often had to take matters into their own hands.

the bear, a show that was dumped unceremoniously on hulu when it first premiered, found a fanbase because a jeremy allen white fan edit featuring him looking broody and hot in the pilot went viral on twitter. that was it. a thirty second video compiling shots of him doing otherwise mundane things like brushing his hair out of his face was all it took to propel him to white boy of the month. everyone came for working class timothee chalamet and stayed to watch a brilliant piece of television audiences might not have otherwise even realized was airing.

fans are not stupid; they know how these algorithms work. it is the weoponization of sex appeal to sell their fave’s latest project. thirst trapping for the arts. i could write a whole other essay about how the fan-edit specifically has changed the way we consume television, how editors are carrying marketing on their backs while massive companies fail to understand how to connect with gen z viewers.

the fan edit is a custom rooted in older online fandom traditions, pre-tiktok. sites like wattpad and tumblr platformed young, horny people indulging in their celebrity-related fantasies out in the open for the first time. fan-fiction featuring the likes of one direction were a dime a dozen and have even been turned into anne hathaway starring films, the birth of the self-insert heroine (a phrase more salacious than i intend it to be, i promise) perhaps being the most explicit sign that watching these stars be hot wasn’t enough; we needed to be a part of the performance too. a participatory audience, more aggressive in expressing their lust upon the object of their sexual fantasies was bred.

take buzzfeed’s now infamous celebrity thirst tweet series. the concept is simple enough. they sit down some attractive celeb and force them to work their way through a tumbler filled with comments left by their fans. here’s the interesting moral dilemma these videos pose though:

thirst is the language of twitter. nobody calls their favorite singer beautiful or sexy anymore. we ask them to: spit on us. step on us. ruin our lives. we need to “speak to them alone, in a room where there are no others.”

someone doesn’t just look good on the red carpet- they took a dip in the mother lake. she’s not fierce, she’s cunt [as a brit, i actually quite like the shallow adoption of the word to remove the sexist sting it used to carry. everyone say thank you to the ballroom culture and black drag queens who birthed this meaning for the word]. we social media users don’t even blink when we see these tweets pop up; we know that this is just how things are said in this alternate realm.

the moment, however, these remarks are removed from their cultural context and read out loud in the real world, these things become crass. this celebrity isn’t some fantastical creature removed from reality, existing only in your imagination- they’re a person who also has access to the internet. the moment they read your thirst tweet out loud, it’s like watching a break in an unspoken social contract. they are forced to see themselves not as a person but as an object.

i call it ‘interneting in real life’. it’s why watching influencers on red carpets bringing up viral tweets is so jarring. our comments simply do not translate if they do not exist in the precarious context of these apps. we perceive our online selves to both be an extension of us and a separate entity entirely. we accept that we curate our presence’s online, but we also say things we would never say in real life. it’s this perceived separation that allows us to so recklessly thirst after some of these people they way we do.

but is it fair on them?

when does thirst turn into sexual harassment? i’d argue getting a deeply uncomfortable shawn mendes to work his way through his thirst tweets blurs that line in a way that is concerning, for instance. removing the language of fandom from it’s digital context has done us little good. just look at how it’s become popular to see brands post online using this language: i don’t care if it makes me ‘the friend who is too woke’: there is no reason why the social media account of a reputable music publication like MTV for instance should ever be referring to an artist as ‘daddy’ on their official account.

lines are being blurred, professionalism and general decorum being lost. there was a time and place for being horny. teenagers sought out covert corners of the internet to express their desires and now everyone is just letting all hang out in the open. after the release of jeremy allen white’s milestone calvin klein ad, a journalist on the golden globes red carpet showed the cast of the bear a blown up picture of white in his underwear and asked:

what went through your head when you saw this?

ayo edibiri, being the perfectly sane person she is, turns the poster around and reminds the reporters they’re “at a work function.” to this day, i have no idea what the intended outcome of the question was. did they think ayo would turn around and compliment the man she works with on his bulge?

it was another case of internet-ing in real life. more and more, we are seeing these boundaries being crossed by reporters, sexualising their subject in the hopes of getting a viral interaction. how uncomfortable you are with how we talk about celebrities online depends entirely on your view of them.

richard dyer (film critic) birthed this notion of ‘star theory’ and altered our reading of modern celebrity along with it. according to him, ‘a star is an image not a real person that is constructed (as any other aspect of fiction is) out of a range of materials (eg advertising, magazines etc as well as films [music]).’ the celebrity- like an object- is easily discardable (we see this in the employment of phrases like ‘khia asylum’ and ‘fall off’), manufactured by their chosen industry to serve a single purpose- “to make money out of audiences who respond to various elements of a star persona by buying records and becoming fans.” just cogs in a capitalistic machine.

if you subscribe to dyer’s theory and view these celebrities as nothing more than meat being packaged for a table of ravenous canivore’s, greedy for skin then the treatment they receive doesn’t matter. does anyone ever ask the cog for consent?

as we watch the justin beldoni case play out, i can’t help but wonder how much of his female fans eagerness to excuse his behavior is rooted in a belief that hearing crass, sexualising, degrading comments about yourself is akin to being complimented. the release of his personal voice notes in which he is clearly overstepping lively’s boundaries have been met with an eagerness online, utilized in the same way erotic audio books are. we have warped what sex and sensuality are and filthied them in our supposed progressiveness online.

the model is the very pinnacle of this of this idea of people as objects, built to project onto for commercial gain. it’s why the exploitation they face is so high. one of the most infamous calvin ads featured mark walhberg (gag) and kate moss who was still a teenager at the time. talking about the shoot, moss said later she experienced “a nervous breakdown” after it was over because she felt so stripped of power.

you felt objectified?” lauren laverne, host of the radio show “desert island discs,” asked moss in 2022.

“yeah, completely. and vulnerable and scared,” she replied. “i really didn’t feel well at all before the shoot. for like a week or two, i couldn’t get out of bed, and i had severe anxiety, and the doctor gave me valium.”

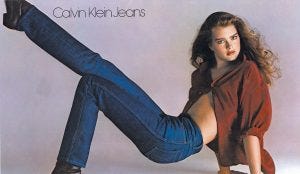

another campaign, shot and directed by richard avedon, included an ad featuring the seemingly suggestive tagline: “you want to know what comes between me and my calvins? nothing” with brooke shields as the model featured. she was only 15 at the time and the papers were already calling her a ‘sex symbol’.

who deserves our protection? i would argue everyone who is placed in vulnerable situations in deserving of some level of care, no matter how much they’re getting paid. there is a lack of empathy, a sort of macabre callousness about how we treat people who are famous. i have always found it absurd that we ask artists to sacrifice so much of themselves and their personal boundaries because they happen to be renowned for doing their job.

i welcome any movement that destigmatizes desire and lust, specifically when it is being lead by women- but there is such a thing as nuance. the same people who ridicule sabrina carpenter and deem her antics whoreish and inappropriate are posting tweets trying to guess the color of their faves dick, down to the shade code (i wish i were making this up). it was once the tabloids jobs to harass these people and reduce them to headline fodder, overstepping boundaries and then turning around, defensive when they’ve been caught.

it seems we’ve taken their place.

hitting the nail on the coffin EVERY. SINGLE. TIME.

YOU!! ARE!! SO!! ENTERTAINING!!! your writing makes me LOCK IN every single time, even more than my favorite book authors lmaooo I always stop EVERYTHING to read you and to give you the PRESTIGE you deserrrveeeee

this place would NOT be the same without you, I love you so much princess!!!!